- Home

- Chris Wooding

The Skein of Lament

The Skein of Lament Read online

THE SKEIN

OF LAMENT

CHRIS WOODING

A Gollancz eBook

Copyright © Chris Wooding 2004

All rights reserved.

The right of Chris Wooding to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in Great Britain in 2004 by

Gollancz

The Orion Publishing Group Ltd

Orion House

5 Upper Saint Martin’s Lane

London, WC2H 9EA

An Hachette UK Company

This eBook first published in 2010 by Gollancz.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 575 08596 1

This eBook produced by Jouve, France

All characters and events in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance

to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor to be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

www.chriswooding.com

www.orionbooks.co.uk

Contents

Cover

Title

Copyright

About the Author

Also By Author

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chris Wooding is the author of sixteen books, which have been translated into twenty languages. In addition to being critically acclaimed, his writing has won a number of awards and his novels are published around the world. In addition to his novels, he writes for film and television, and has several projects in development. He lives in London.

Learn more about Chris Wooding at www.chriswooding.com

Also by Chris Wooding in Gollancz:

The Weavers of Saramyr: Book One of The Braided Path

ONE

The air, cloying and thick from the jungle heat, swam with insects.

Saran Ycthys Marul lay motionless on a flat boulder of dusty stone, unblinking, shaded from the merciless sun by an overhanging chapapa tree. In his hands was a long, slender rifle, his eye lined up with the sight as it had been for hours now. Before him a narrow valley tumbled away, a chasm like a knife slash, its floor a clutter of white rocks left over from a river that had since been diverted by the catastrophic earthquakes that tore across the vast, wild continent of Okhamba from time to time. To either side of the chasm the land rose like a wall, sheer planes of prehistoric rock, their upper reaches buried beneath a dense complexity of creepers, bushes and trees that clung tenaciously to what cracks and ledges they could find.

He lay at the highest end of the valley, where the river had once begun its descent. The monstrosity that had been chasing them for weeks had only one route if it wanted to follow them further. The geography was simply too hostile to allow any alternatives. It would be coming up this way, sooner or later. And whether it took an hour or a week, Saran would still be waiting.

It had killed the first of the explorers a fortnight ago now, a Saramyr tracker they had hired in a Quraal colony town. At least, they had to assume that he had been killed, for there was never any corpse found nor any trace of violence. The tracker had lived in the jungle his whole adult life, so he had claimed. But even he had not been prepared for what they would find in the darkness at the heart of Okhamba.

After him had gone two of the indigenous folk, Kpeth men, reliable guides who doubled as pack mules. Kpeth were albinos, having lived for thousands of years in the near-impenetrable central areas where the sun rarely forced its way through the canopy. Sometime in the past they had been driven out of their territory and migrated to the coast, where they were forced to live a nocturnal existence away from the blistering heat of the day. But they had not forgotten the old ways, and in the twilight of the deepest jungle their knowledge was invaluable. They were willing to sell their services in return for Quraal money, which meant a life of relative ease and comfort within the heavily defended strip of land owned by the Theocracy on the north-western edge of the continent.

Saran did not regret their loss. He had not liked them, anyway. They had prostituted the ideals of their people by taking money for their services, spat upon thousands of years of belief. Saran had found them eviscerated in a heap, their blood drooling into the dark soil of their homeland.

The other two Kpeth had deserted, overcome by fear for their lives. The creature used them later as bait for a trap. The tortured unfortunates were placed in the explorers’ path, their legs broken, left cooking in the heat of the day and begging for help. Their cries were supposed to attract the others. Saran was not fooled. He left them to their fates and gave their location a wide berth. None of the others complained.

Four more in total had been killed now, all Quraal men, all helpless in the face of the majestic cruelty of the jungle continent. Two were the work of the creature tracking them. One fell to his death traversing a gorge. The last one they had lost when his ktaptha overturned. The shallow-bottomed reed boat had proved too much for him to handle in his fever-weakened state, and when the boat righted itself again, he was no longer in it.

Nine dead in two weeks. Three remaining, including himself. This had to end now. Though they had made it out of the terrible depths of central Okhamba, they were still days from their rendezvous – if indeed there would even be a rendezvous – and they were in bad shape. Weita, the last Saramyr among them, was still shaking off the same fever that had claimed the Quraal man, he was exhausted and at the limit of his sanity. Tsata had picked up a wound in his shoulder which would probably fester unless he had a chance to seek out the necessary herbs to cure himself. Only Saran was healthy. No disease had brushed him, and he was tireless. But even he had begun to doubt their chances of reaching the rendezvous alive, and the consequences of that were far greater than his own death.

Tsata and Weita were somewhere down the valley in the dry river bed, hidden in the maze of moss-edged saltstone boulders. They were waiting, as he was. And beyond them, similarly invisible, were Tsata’s traps.

Tsata was a native of Okhamba, but he came from the eastern side, where the Saramyr traders sailed. He was Tkiurathi, an entirely different strain to the albino, night-dwelling Kpeth. He w

as also the only surviving member of the expedition capable of leading them out of the jungle. In the last three hours, under his direction, they had set wire snares, deadfalls, pits, poisoned stakes, and rigged the last of their explosives. It would be virtually impossible to come up the gorge without triggering something.

Saran was not reassured. He lay as still as the dead, his patience endless.

He was a strikingly handsome man even in this state, with his skin grimed and streaked with sweat, and his chin-length black hair reduced to sodden, lank strips that plastered his neck and cheeks. He had the features of Quraal aristocracy, a certain hauteur in the bow of his lips, in his dark brown eyes and the aggressive curve of his nose. His usual pallor had been darkened by long months in the fierce heat of the jungle, but his complexion remained unblemished by any sign of the trials he had endured. Despite the discomfort, vanity and tradition forebade him to shed the tight, severe clothing of his homeland for attire more suited to the conditions. He wore a starched black jacket that had wilted into creases. The edge of the high collar was chased with silver filigree which coiled into exquisite openwork around the clasps that ran from throat to hip along one side of his chest. His trousers were a matching set with the jacket, continuing the complex theme of the silver thread, and were tucked into oiled leather boots that cinched tight to his calves and chafed abominably on long walks. Hanging from his left wrist – the one which supported the barrel of his rifle – was a small platinum icon, a spiral with a triangular shield, the emblem of the Quraal god Ycthys from whom he took his middle name.

He surveyed the situation mentally, not taking his eye away from the grooved sight. The point where the gorge was at its narrowest was laden with traps, and on either side the walls were sheer. The boulders there, remnants of earlier rockfalls, were piled eight feet high or more, making a narrow maze through which the hunter would have to pick its way. Unless it chose to climb over the top, in which case Saran would shoot it.

Further up the rising slope, closer to him, the old river bed spread out and trees suddenly appeared, a collision of different varieties that jostled for space and light, crowding close to the dry banks. Flanking the trees were more walls of stone, dark grey streaked with white. Saran’s priority was to keep his quarry in the gully of the river bed. If it got out into the trees . . .

There was an infinitesimal flicker of movement at the far limit of Saran’s vision. Despite the hours of inactivity, his reaction was immediate. He sighted and fired.

Something howled, a sound between a screech and a bellow floating up from the bottom of the slope.

Saran primed the rifle again in one smooth reflex, drawing the bolt back and locking it home. He had a fresh load of ignition powder in the blasting chamber, which he counted as good for around seven shots under normal conditions, maybe five in this humid air. Ignition powder was so cursedly unreliable.

The jungle had fallen silent, perturbed by the unnatural crack of gunfire. Saran watched for another sign of movement. Nothing. Gradually, the trees began to hum and buzz again, animal whoops and birdcalls mixing and mingling in an idiot cacophony of teeming life.

‘Did you hit it?’ said a voice at his shoulder. Tsata, speaking Saramyrrhic, the only common language the three survivors had left.

‘Perhaps,’ Saran replied, not taking his eye from the sight.

‘It knows we are here,’ Tsata said, though whether he meant because Saran had fired at it or not was unclear. He was a skilled polyglot, but not adept enough at the intricacies of Saramyrrhic inflection, which were practically incomprehensible to someone who was not born there.

‘It already knew,’ murmured Saran, clarifying. The hunter had shown uncanny prescience thus far, having managed to get ahead of them numerous times, guessing their route and ignoring the decoys and false trails they had left. It was only Tsata who had even seen it at all, two days ago, heading after them into the gorge. Neither Tsata nor Saran had been under any illusion that their traps would catch it by surprise. They could only hope that it would simply be unable to avoid them.

‘Where is Weita?’ Saran asked, suddenly wondering why Tsata was here and not down among the boulders, where he was supposed to be. Sometimes he wished Okhambans had the same ingrained discipline as Saramyr or Quraal, but their anarchic temperament meant that they were never predictable.

‘To the right,’ Tsata said. ‘In the shadow of the trees.’

Saran did not look. He was about to form another question when a dull blast thundered up the gorge, making the trees shiver and the rocks tremble. From the midst of the river bed, a thick cloud of white dust rose slowly into the air.

The echoes of the explosion pulsed away into the sky, and the jungle was silent once again. The absence of animal sounds was eerie; in the months they had been travelling, it had been a constant background noise, and the quiet was an aching void.

For a long moment, neither of them moved or breathed. Finally, the shifting of Tsata’s shoe on stone broke the spell. Saran risked a glance back at the Tkiurathi, who was crouching next to him on one knee, hidden against the smooth bark of the chapapa that sheltered them both.

No words were exchanged. They did not need them. They simply waited as the rock dust cleared and settled, then resumed their watch.

Despite himself, Saran felt a little more at ease with his companion at his side. He was strange in appearance and even stranger in attitude, but Saran trusted him, and Saran was not a man who trusted anyone easily.

Tkiurathi were essentially half-breeds, born of the congress between the survivors of the original exodus from Quraal over a thousand years ago, and the indigenous peoples they found on the eastern side of the continent. Tsata had the milky golden hue that resulted, making him seem alternately healthy and tanned or pallid and jaundiced, depending on the light. Dirty orange-blond hair was swept back along his skull and hardened there with sap. He wore a sleeveless waistcoat of simple greyish hemp and trousers of the same, but where he was not covered up it was possible to see the immense tattoo that sprawled across him.

It was a complex, swirling pattern, green against his pale yellow skin, beginning at his lower back and sending tendrils curling up over his shoulder, along his ribs, down his calves to wrap around his ankles. They split and diverged, tapering to points, rigidly symmetrical on either side of the long axis of his body. Smaller tendrils reached up his neck and under his hairline, or slid along his cheek to follow the curve of his eye sockets. Two narrow shoots ran beneath his chin, hooking over to terminate at his lip. From within the tattoo mask that framed his features, his eyes were searching the gorge beneath them, their colour matching the ink that stained him.

It was perhaps an hour later that Weita joined them. He looked sickly and ill, his short dark hair lustreless and his eyes a little too bright.

‘What are you doing?’ he hissed.

‘Waiting,’ Saran replied.

‘Waiting for what?’

‘To see if it moves again.’

Weita swore under his breath. ‘Didn’t you see? The explosives! If they didn’t kill it, then one of the other traps must have.’

‘We cannot take the chance,’ Saran said implacably. ‘It may be only wounded. It may have triggered the trap intentionally.’

‘So how long do we sit here?’ Weita demanded.

‘As long as it takes,’ Saran told him.

‘Until the light begins to fail,’ Tsata said.

Saran accepted the contradiction without rancour. Privately, he was worried that the creature had already slipped up the gorge under cover of the boulders and made it to the treeline, although he counted it unlikely that it could have done so without him catching a glimpse of it. After sunset, it would have the advantage of shadow, and even Tsata’s dark-adapted eyes would be hard pressed to pick it out at such a distance.

‘Until then,’ Saran corrected himself.

But though insects bit them and the air dampened until it took noticeably more effort

to breathe, their vigil went unrewarded. They did not see another sign of their pursuer.

Weita’s protests fell on deaf ears. Saran could wait forever, and Tsata was content to be as safe as possible in this matter. His concern was the welfare of the group, as it always was, and he knew better than to underestimate their pursuer. But Weita griped and complained, eager to get down among the rocks and see the corpse of their enemy, eager to dispel the fear of the creature that only Tsata had seen so far, the invisible agent of vengeance that had grown in Weita’s imagination to the stature of a demon.

Finally, an hour before sunset, Tsata shifted against the trunk of the chapapa and murmured. ‘We should go now.’

‘At last!’ Weita cried.

Saran got up from where he had been lying on his chest for almost the entire day. In the early days of the expedition, Weita had marvelled at the endurance of the man; now it merely irritated him. Saran should have been racked with pain by now, but he seemed as supple as if he had just been for a stroll.

‘Weita, you and I will spread out through the rocks and come in from either side. You know where the traps are; be careful. The explosion may not have set them all off.’ Weita nodded, only half-listening. ‘Tsata, stay high. Go over the top of the boulders. If it tries to shoot or throw anything at you, drop down and head back here as fast as you can.’

‘No,’ said Tsata. ‘It may already be in the trees. I will be an easy target.’

‘If it has escaped the gorge, then we are all easy targets,’ Saran answered. ‘And we need someone up there to look out for it.’

Tsata thought for a moment. ‘I understand,’ he said. Saran took that to mean he agreed with the plan.

‘Do not let your guard down,’ Saran advised them all. ‘We must assume it is still alive, and still dangerous.’

Tsata checked his rifle, refilled and primed it. Saran and Weita hid theirs in the undergrowth. Rifles would only be a hindrance in the close quarters of the river bed. Instead, they drew blades, Weita a narrow, curved sword and Saran a long dagger. Then they moved out of hiding and went among the rocks.

The Skein of Lament

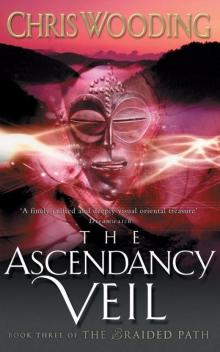

The Skein of Lament Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil

Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil The Ace of Skulls

The Ace of Skulls The Iron Jackal

The Iron Jackal The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray

The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil Storm Thief

Storm Thief Silver

Silver Pale

Pale Poison

Poison Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament

Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament The Ember Blade

The Ember Blade The Black Lung Captain

The Black Lung Captain Out of This World

Out of This World The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3

The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3 The Fade kj-2

The Fade kj-2 The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path

The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path Retribution Falls totkj-1

Retribution Falls totkj-1 The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls

Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls The Black Lung Captain totkj-2

The Black Lung Captain totkj-2 The Iron jackal totkj-3

The Iron jackal totkj-3 The Ace of Skulls totkj-4

The Ace of Skulls totkj-4 The ascendancy veil bp-3

The ascendancy veil bp-3