- Home

- Chris Wooding

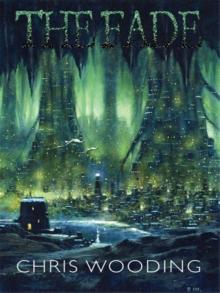

The Fade kj-2 Page 10

The Fade kj-2 Read online

Page 10

Down, down, away from the killing dawn. The world I know opens its arms to me, and darkness clasps me to its chest.

12

We're moving.

It's the first thing I notice, even before I open my eyes to see the soft bed I'm lying in. The blankets are of a downy material I don't recognise. A curtain of furred hide surrounds the square bed, sealing me into my own small world. Music is coming from beyond, wind instruments cooing over the sporadic pluck of strings.

That's when I realise I'm not dead.

I don't try to stir myself. I just stare at the ceiling, where arched beams support a curved wooden roof, and think of nothing. I don't feel relieved, or happy, or thankful. Just peaceful. So I lie there for a long time, listening to the music. The air is cool on my face. Tears creep from the outside corners of my eyes, trickling down towards my ears. I don't know where they're coming from, but they come anyway.

After a while, I try to work out where I am. It's some kind of room, and big; I can tell that by the acoustics. But the sensation of movement puzzles me, a gentle and irregular up-and-down swaying and the occasional bump from below. It doesn't feel like water, so we're not on a ship. It feels like we're travelling over land, but the room sounds far too big to be any kind of wagon or cart.

My fingers brush against my thigh and I feel an unfamiliar fabric there. Stirred by curiosity, I raise the blankets and look down at myself. I'm shocked by how much effort it takes to hold them up. My body smells of scented oils, delicate and bitter.

I'm wearing a pale green slip, dyed with angular patterns along its length. It's the patterns, more than anything else, that put the whole picture together for me. I remember seeing similar patterns at a bazaar in Veya, on artefacts that were being sold as genuine SunChild merchandise. I had been sceptical, and doubly so when I saw the outrageous price. But now I wondered.

I'm with the SunChildren. Feyn has brought me to his people.

I lie back. The insidious tingle on my skin has gone. The agonising pain and delirium seems like a nightmare, fading in the face of wakefulness. I've passed through the Shadow Death.

Eventually thoughts begin to intrude, and the fragile tranquillity I felt begins to come apart. Thoughts of Jai, of Rynn, of our escape from Farakza. So I raise myself on one trembling elbow, and I part the hide curtain a little.

I'm in a small hall, made of varnished rootwood or something similar. My bed is one of four, occupying the corners of the room. The other three have their curtains drawn back and are empty. Patterned hangings decorate the walls, low tables beneath them. One side of the room is evidently a food preparation area of sorts, with a small metal stove, a chopping surface and knives and plates gently rattling in their racks. Glass globes set on heavy stone bases glow from within, and several large areas of wall are covered by flaps of thick brown hide. I guess that they work as windows when they're open, but it's a little chilly and they've been fixed shut.

There are six SunChildren here, sitting in a circle on a large mat in the centre of the room. Three men are playing instruments, the other three – an old woman and two small girls – are watching. I'm surprised to see that one of the wind instruments – a kind of flute fashioned from a reed – is being played by Feyn.

Their skin is uniformly black, and both men and women wear their hair in oiled ringlets. They're small and willowy in stature, wearing robes of unfamiliar weave, something like silk. Each robe is stitched with the most marvellous designs. Some show sun-rays and landscapes and animals and people, evidently depicting a story. Others are more abstract but no less beautiful, with bold, jagged shapes and curling embroidery. The craftsmanship is dazzling.

I watch Feyn play for a short while, before one of the children notices me and points, exclaiming excitedly in their percussive tongue. Feyn breaks off from the melody immediately, puts down his flute and hurries over. The others dissolve into chatter, and the old woman has to physically restrain the children from running towards me.

Feyn pushes back the curtain, his dark eyes sparkling. 'Welcome back,' he grins, and that makes me smile too.

'So that was the Shadow Death, hmm?' I say. 'Don't know what all the fuss is about.'

He laughs, almost hugs me, hesitates, then does it anyway as best he can with me lying down. The others in the room make celebratory cries, a high yi-yi-yi!

'You have been spared by the suns,' he says.

'No,' I reply. 'I beat them.'

Feyn turns back to the others and chatters off a rapid string of syllables, punched with the back-of-the-throat click that characterises their language. Relaying what I just said. The others break up laughing, and one of them slaps his upper arm repeatedly in what I take to be appreciation of my comment.

'Is this your-' I begin, then realise I've forgotten the word he used.

'My coterie? Now it is.'

'How did you get me here?'

'I made a signal,' he replied. 'I will show you how, when you are strong again. They followed my signal, and they found me.' He strokes my hair tenderly. 'I had to leave you several times, to climb out of the basin and tend to my signal. Each time I was afraid something would find you before I returned. It is not good to be helpless in that place.'

'You did fine,' I say, and I lie back on the pillows. 'You did fine.'

Suddenly I feel light-headed, and I have an overpowering urge to sleep. I'm weaker than I thought. Feyn understands, of course. He runs his fingers along the line of my jaw, touching me like a lover, and then retreats and closes the curtain behind him. I can hear the children's frantic questions and Feyn's patient answers, fading away as I fall into the plush folds of oblivion. I wake and it's bright. That gives me a shock. I know that light. It's daytime.

Feyn is lying in bed next to me, his thin shoulders rising and falling in slumber. I'm mildly surprised by that, too, but it pales in comparison to the proximity of the suns' light. And yet we're still moving. These people travel during the day?

At first I don't dare move. Instinct tells me I should burrow under the blankets and hide. But whereas before I would have panicked, after passing through the Shadow Death it seems ridiculous. Gradually I calm myself. The brightness is coming from outside the curtains, but it's not strong enough to be direct sunlight. Before I can think myself out of it, I part the curtain and look.

The room beyond is deserted, and the other three beds have their furred curtains drawn. The hide flaps on the walls burn with white light: the sun is beating on them from the outside. There are two on each flank of the hall.

I look for a while longer. The light in the room doesn't seem to be threatening. I couldn't say why, but the hide flaps have robbed it of its danger. Still, I don't trust it enough to leave my haven, so I let the curtain fall closed again. It's only then I notice what's on the inside of my wrist.

I stare at the symbol, bewildered. Two chevrons pointing toward my hand, shot through with three vertical lines. I rub at it with my thumb. It's been skinmarked: painted in with dye and then chthonomantically bonded so that it will never fade. Back in Veya, we have dweomings who do this kind of thing, or chthonomancers for the rich. The Gurta have Elders, that could do it if body modification wasn't forbidden by one of their many fucking stupid Laws. It seems that the Far People have their own way of tapping rock-magic, then. Interesting. I wonder what the symbol means. Given what I've seen of these people, I doubt it's anything but benevolent.

Just being awake tires me out. The warmth of the suns has raised the temperature in the hall to a drowsy heat. I nestle back into the covers and slide close to Feyn. His back is to me, so I fit myself against him, my arm across his ribs. His fingers sleepily entwine with mine, but I know by the depth of his breathing that he hasn't woken.

I lie against him, his thin body unfamiliar. Rynn was bulky and hairy; Feyn is slender and smooth. I think back on that kiss and I still don't know why I did it. I can't even bring myself to be hurt or embarrassed by his rejection. I was exhausted and frightened and right

then I wanted something to take away the pain. Someone to touch me kindly, someone to need me. Because my husband was gone, and my son was so far away.

And yet I can't help wondering what he's doing in bed with me. Is it the custom of his people to share beds? Were they short on space? Or is it something else? Something more?

And is that what I want?

I'm appalled at myself for even thinking about it. Liss and Casta would have paroxysms of joy if they could see me now. The boy is my son's age.

I don't let him go, not straight away. I tell myself there's nothing erotic in it. It's just the comfort I need. The feel of another person. If I believe that, I can stay this way a little longer.

But in the end I can't. I can't keep Rynn out of my head. All the times I slept with other men in the service of my Clan, none of them felt as wrong as this. Because Rynn is dead now, and because this boy isn't a fade like the rest were. My husband looms larger in my memory than he ever did in my life. I feel disloyal for even contemplating the absurd possibility of being with Feyn.

I draw away from him, away from his warmth. Voids, the thing I miss most is being held by my husband, the feeling of protection. I miss feeling like a little girl, safe from the world in daddy's arms.

In that moment, it hits me that I'll never be held by him again, and I quietly cry myself back to sleep. It's night when my eyes open, and Feyn isn't there. The motion of the hall is more noticeable now, bumpier. I hear the SunChildren talking and the sound of rapid chopping. I smell food and I realise that I'm ravenous. I've lost a lot of weight during my convalescence.

At the first twitch from the curtain, the children come running over to look at me. I smile at their wary fascination. The old woman bundles them away, scolding, as Feyn comes over with a plate of food. It's a kind of warm mush of sugary pulp with seeds and other, less identifiable things mixed in.

'You should eat,' he says, though I need little prompting.

'With my hands?' I ask, noting the lack of cutlery.

'That is our way,' he replies.

I'm fine with that. I scoop the mush into my mouth. It's way too sweet, but I could stomach just about anything right now. When I'm finished, I ask if he's got any more.

'Too much will make you ill. Be slow,' he says.

The food has woken me up, and I look about, suddenly restless. 'We're still moving,' I say.

'Yes.'

'Where are we?'

Feyn offers his hand. 'Do you think you can stand?'

I push the blankets off. 'I can try.'

He helps me up. I get a dizzy rush, but it passes. I walk carefully across the room, with Feyn at my shoulder steadying me. The men murmur greetings, to which I reply with a nod. We go over to one of the windows. I see that the hide flaps have been pinned back, revealing inverted triangular holes with no glass in their frames.

I look out, and then I understand.

The palette of the night is haunting greens, faint blues, ethereal purples. It's brighter than I would have thought: the stars that pack the sky spread a cold glow across the broken surface of the rock plains. Distant thunderheads mar an otherwise empty horizon, flickering from within. The landscape is desolate and alien: rock formations rear up like monsters breaching a petrified sea. In the distance, mountains slope into rugged peaks, forested with mycora and lichen trees and foliage I've never seen before. A distant flock of flying creatures soar on membranous wings over the canyons that cut the plains.

I have to step back quickly, staggered by a sense of vertigo. That eternal glittering nothingness overhead threatens to overwhelm me. But I remind myself that I have a roof over my head, and I make myself go back, dragged by the wonder of the world beyond the window. And as I stand amazed, the terror begins to recede. My body and brain are starting to understand that I'll come to no harm. Old, old instincts are asserting themselves again. The instincts of my ancestors, who lived and died beneath a ceiling of stars.

I had dismissed the possibility that this moving room was being pulled like a wagon, simply because it was too big. I was wrong. They're being pulled in chains of five or six: wide, low constructions with rounded roofs covered in some kind of reflective black carapace. Charms and totems dangle from overhanging eaves. Each carriage in the chain is built on a stout wooden platform, below which several sets of enormous rollers turn slowly, grinding over the stony ground.

But it's the creatures at the head of each chain that make me catch my breath. I know them immediately. They're called gethra. They were Reitha's particular field of interest, and she never tired of talking about them. Her dream was to study the gethra herds once she had qualified as a naturalist. Suddenly I can see the fascination. I've never in my life beheld any land animal so colossal.

They're like moving pieces of the landscape: almost featureless humps, rising out of the earth. Long, segmented tails drag behind them, armoured in the same dusty, scratched black stuff as their shells and ending in a wide fan that brushes over their trail as they lumber forward. Every other part of them is hidden, but I know that beneath that canopy of armour, massive crablike legs move steadily in sequence, working together to haul their tremendous bulk. The carriages are attached by a complicated series of chains and ropes, some attached to bolts driven into the gethra's shell, some disappearing underneath.

As I stare, I realise I shouldn't have been surprised that the SunChildren can travel during the day. Their whole society has depended on foiling the deadly touch of the suns. They have methods I can only guess at, special techniques for sunproofing material and access to resources unknown to the world below. Creatures like the gethra have adapted to life under the suns and evolved protection from their light. No doubt the SunChildren have copied nature's designs over the millennia. With all that time to learn, and the advantage of superior intelligence, is it any wonder that they have mastered the suns as well as the animals have?

'Where are we going?' I ask Feyn.

'Turnward,' he says.

We're heading towards Jai. Turnward of Farakza is the Borderlands, and beyond that is Eskara.

It's as if he's read my thoughts. 'In several days' time, we'll pass near a cave network that will take you down into the Borderlands. The Pathfinders have agreed to divert the caravan a little way to take you there.'

'And you?' I ask, turning towards him.

'I will stay. I have spoken with the Loremaster of this coterie. I understand now I was foolish. There are reasons why my kind must be…' he struggles '… aloof?' I nod my approval. He's really getting good. He smiles and continues. 'I will study further on Eskaran, because I know more now. Then perhaps I will travel to a far away outpost, where there are Eskarans, and I will learn more. When I am older and more wise, I will speak with others at the gatherings, and seek to be sent to the heart of your lands.'

I feel an uneasy mix of sadness and relief at his words. I know he'll be safe, and that's what counts; but it's an unexpected wrench to realise that I'll be leaving him behind and that I'll never see him again. Perhaps he knew it would be that way. Perhaps that's why he didn't return my kiss.

Stop thinking about it. It can't happen.

I turn over my hand to show him the sigil on the inside of my wrist. 'What's it mean?' I ask.

'It means you are a friend to the SunChildren,' he says. 'It means you belong to a coterie. Only a few outsiders have ever been given this gift.' He looks over at me with those huge black eyes. 'It means you can stay. If you want.'

I stare through the window at the panorama before me. Beautiful, frightening and strange. A world without limits. A new start. Voids, I can't deny that it's tempting. More than tempting. There's a great desolation in me and I'm yearning to sever my ties to its source forever: from my masters, from my life, from all the memories of Rynn.

'You said, just before the Shadow Death took me, that one way or another I'd be free,' I murmur.

'Yes,' he says, and that's all.

I think about that for a time. It's an attr

active idea. To stay here. Cut loose. Never look back.

But an idea is all it is, a fantasy, like my dreams of a peaceful life. Because there's still Jai. He's still down there. I've not come this far to stop now. It was my son that got me out of that prison, and it's my son who'll keep me going.

'I wish I could, Feyn,' I say, and I mean it. I really wish I could. But all my choices were made long ago.

13

Time is slippery and unreliable. I wake and sleep and it's hard to tell the difference. Fevered nightmares curdle with the hallucinations that cloud my eyes when they're open. Sometimes I'm aware of the shelter of the rock, of Feyn sitting next to me and talking. Other times I'm flitting through a world of horrors, bewildered, consumed by pain. Moments of lucidity float like windows on a sea of delirium.

Faces from my past loom up at me, distorted. Master Allet, Aila, Keren, Chorik. Someone saying a name, over and over. Belek Aspa. Voids, where do I know that name from?

At some point I feel my stomach clench and its contents come rushing up my throat to fill my mouth. Feyn is there to clean my face, but afterward he makes me eat again, and I throw it up again, which clears my head a little. He makes me eat a third time, and I keep it down.

I can sense large things moving about in the undergrowth beyond my bunk of stone, soil and vines, but whether they are real or not I can't tell. Insects creep on the edge of my vision and crawl up my arms and into my hair. Feyn tells me they're just the pricking of my nerves given shape by my tortured mind. It doesn't help.

It's impossible to get comfortable. Moving is a torment as my bones seem to grind against each other. The sickness crawls beneath my skin, fighting to burrow deeper while my body struggles to cast it out. It's a black, oily, vile thing, a taint in my veins.

Somehow, in amongst it all, I find the lucidity to begin a chant. At first it comes brokenly, in bits and pieces, but in time the phrases link up, form a chain and hold solid. I sink into a shallow trance. I have to drive out the taint. It's the only way I'll make it through.

The Skein of Lament

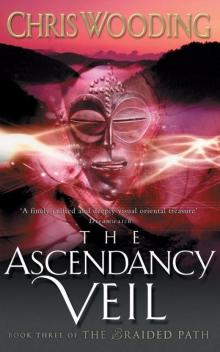

The Skein of Lament Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil

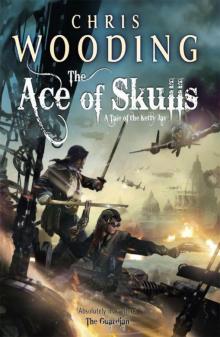

Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil The Ace of Skulls

The Ace of Skulls The Iron Jackal

The Iron Jackal The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray

The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil Storm Thief

Storm Thief Silver

Silver Pale

Pale Poison

Poison Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament

Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament The Ember Blade

The Ember Blade The Black Lung Captain

The Black Lung Captain Out of This World

Out of This World The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3

The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3 The Fade kj-2

The Fade kj-2 The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path

The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path Retribution Falls totkj-1

Retribution Falls totkj-1 The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls

Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls The Black Lung Captain totkj-2

The Black Lung Captain totkj-2 The Iron jackal totkj-3

The Iron jackal totkj-3 The Ace of Skulls totkj-4

The Ace of Skulls totkj-4 The ascendancy veil bp-3

The ascendancy veil bp-3