- Home

- Chris Wooding

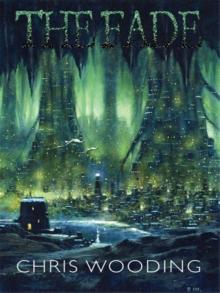

The Fade kj-2 Page 13

The Fade kj-2 Read online

Page 13

The shaft begins to switch back on itself as we near the top, broken by some ancient quake. It tightens dramatically, so much that we can barely fit through. I'm worried Feyn will freeze up in there. Claustrophobia's not unheard of even among my people; it must be worse for his.

He takes a deep breath, lets it out, and squeezes through the fissure. I don't know what keeps him going, but though he's as tired as I am he's showing no signs of giving up.

The fissure takes us up almost a hundred spans before it widens again suddenly. I clamber out to find Feyn heading away along a sloping tunnel. It's the back end of a cave, wide enough for six men abreast. Cracked bones and a rotted nest of scrub attest to an animal that once lived here, but it's abandoned and empty now.

'We are close,' Feyn declares, his voice numb with weariness.

We follow the thin stream to a spring bubbling in a hollow in the stone. I catch up with Feyn as he drinks.

'Can you smell the air?' he asks me, and I can. It's warm, arid, unfamiliar.

We travel on. The cave splits into other caves, and we're forced to choose carefully. We can hear creatures calling to each other in the depths. Deep booming sounds, like Craggens but without the suggestion of language and structure.

Some time after, still following the breeze, we find a short vertical ascent. Feyn struggles up it first, and when I get to the top I find him sitting on the floor next to me, his thin ribs heaving beneath his ragged shirt.

But there's something else. I sense it even before I see it. About thirty spans ahead of us is a corner, and the stone at the end burns with white light.

Daylight.

I shield my eyes, which are blurring with tears. Dazzling after-images make it difficult to see. A primal, irrational fear uncoils within me. To be so close to raw daylight terrifies me. I'm afraid it will somehow flood in and consume us. I start to regret letting Feyn talk me into this course of action.

'Now what?' I ask him.

'Now we wait.'

'You brought us all the way up to the surface and now we wait? That's your plan?' I demand of him.

'Yes. We wait until the sky becomes dark.'

'There are Gurta right behind us, Feyn! They'll be here in minutes! ' I turn away from the light, searching for a way out of our predicament. I can't believe he's done this to us. I can't believe I trusted him. 'Let's go back. Into the caves. They can't track us without the raka.'

'They are too close behind us.'

He's right. There haven't been any branches off this tunnel for quite a way. We'll only end up running into the Gurta and hastening the inevitable. But still-

'You don't want to try?'

He shakes his head.

I want to be furious, but I can't manage it. I want to keep struggling, but his calm is infectious. I can't stand that we're so fucking close and we've been thwarted. I want to keep running, out into the sun or onto the swords of the Gurta, and yet his acceptance of the end cools me. Shrill hysteria and urgent demands seem out of place now. I'm too tired.

I sit down next to Feyn. For a long time, neither of us says anything. I'm the one to break the silence.

'We could hold them off here. At the top of this cliff.'

Feyn gives me another one of those parent-child looks, as if to say: now is that really true? And it's not. I could have held them off back at the fissure, but they'll be through that by now. There'll be archers to cover the Gurta climbing up the cliff, and they'll kill me the instant I show my face.

'You never finished your story,' I say.

He makes a quizzical noise.

'The s'Tani. The Old Men, when we were all one race.'

'You remembered,' he says, and gives me that heartbreaking smile of his. Voids, it's beautiful when the boy smiles.

He settles himself and begins. When he speaks, it's like a teacher to a pupil. I recall his ambition to be the first of the Far People to attend Bry Athka University, and I see for the first time that he might make a good Masterscholar.

'A long time ago, there were the s'Tani and the a'Jaka'ai – the underdwellers, whom now you know as the Umbra, the Craggens and the Ya'yeen. They grew in the dark, but the s'Tani grew beneath the suns. They walked naked under the skies, and the touch of the light was warm.

'Then the suns grew cruel. The sickness began, and in anger the s'Tani blamed each other. Instead of one people, they became many people. They went underground then. The Gurta, the Banchu, the Khaadu, and the forty tribes of Eskara whose names you still carry long after the blood has been mixed.'

'It's not mixed so much,' I tell him. 'You can still see the bloodlines. Rynn was Venya, they're always built like crayls, with broad faces. Fentha still have red hair and eyes. Nathka have beautifully proportioned features.'

'And yours? You are of the tribe of Massima.'

'Small, hair very black, brown eyes, dusky skin – I'm a typical Massima. Besides, we cheat. A child can take the tribal name of either the mother or the father. We pick the one most suitable.'

'Your son?'

'Massima,' I say. 'He was never a Venya. Go on with the story.'

'The people went underground, but some would not give up the sky. They called themselves a'Sura'Sao, which you call the SunChildren. They hoped to endure the sickness, to become…' He waves his hand, searching for the word.

'Immune?'

'Yes. Like other sicknesses, we thought some would resist it. Many would die, but the survivors would be strong forever against it. And they said ''We will show our brothers and sisters that we should not hide from the light. It is better to die here than live down there. They will remember us, and they will come back, and we will bring them here to live beneath the sky.'' '

'Didn't work out that way,' I say, looking out over the edge of the wall. I can hear Gurta voices in the distance, jabbering at each other. Gurta never could shut up. Suicidally tenacious yet hopelessly disorganised.

'Many died before we realised that the sickness was not like other sickness,' he continues. 'And it was getting worse. But we learned how to live, for we would not go below. And we waited for our brothers and sisters to come back, so we could show them.'

'But they never came.'

'They came back, but by then they had forgotten us. We greeted them and they slaughtered us. They saw savages and they were afraid.'

'Was that us? The Eskarans?'

'We do not recall. Back then, we did not know the differences between you. So then it was decided. We would let you make your own learning. You did not deserve help from us.' He makes a gesture that approximates a shrug. 'We visit only the most remote places of your people, to trade for what we need. But we do not stay long.'

'Ignorance equals division,' I say. 'Welcome to the world.'

'You know this, and you hate the Gurta anyway.'

'I have a right. They killed my husband. They enslaved me as a child.'

'There is more,' he says. 'They have done other things.'

I don't know how he surmised that; his talent for perception is frightening. I nod, but that's all.

'And yet you admire them.'

'Yes!' I snap at him. 'Yes. Who wouldn't? I've lived among them. They have culture and poetry and wonderful things, devices and songs and stories that can pull your heart from your chest. And yet they're stuck in this ancient prison of laws and rules that means we'll never see eye to eye, we'll never stop fighting. We'll only ever understand them when our scholars are picking over the bones of their once-mighty cities, and then we'll lament the loss of a great culture, feel terrible about its destruction and then pick another fucking fight and go do it again!'

I realise I've raised my voice and the Gurta can probably hear me. Feyn has a way of prodding sore spots. I'm almost certain he does it on purpose.

'I detest having to acknowledge the good points,' I say, quieter. 'Hate should be clean, in and out like a blade. You can't let yourself admire your enemy or you lose the will to kill them.'

Feyn looks down at the ground between his

knees, his manner thoughtful. 'We have a saying. The translation is: Hate is like fire. If you embrace it, it consumes you.'

I almost make a scornful comeback and then stop myself. Pithy sayings are all very well, but good advice that you can't take is just irritating. Stop hating, he says. So simple. And while I'm doing that, I'll change the day to night.

The thought has barely crossed my mind when the light from outside begins to dim. Disbelief makes me doubt my hold on reality.

'Ready to go?' Feyn asks, getting to his feet.

I can only gape. The world is darkening before my eyes.

'What is it? What's happening?' I ask as I stand.

'Halflight,' he says.

'You knew? All this time underground and you still knew when halflight was coming?'

'It is life and death to us,' he says. 'It is instinct.'

The release of a bowstring reaches me a fraction of an instant before the arrow arrives, but that time is long enough for me to pull him down. The arrow skims close enough to part the hair on the side of his skull. An explosive curse comes from the darkness of the cave behind us.

We run. The light is dying as we plunge towards it. A second arrow ricochets from the cavern wall, rattling at our feet.

We round the corner at a sprint, and with that, we race out of my world and enter his.

16

I can hear someone calling my name amid the din in my head. The blackness is total and it's burning hot. As the ringing in my ears starts to fade, I can make out the voice, and for a moment I really believe that it's Jai calling. I'm dead and he's coming to me like the fireclaw visions of a dweoming.

Then my eyes flutter open.

I'm flat on my back on the surface of the river. The heat is excruciating. I've been carried a short distance on the flow, and I can see Feyn, halfway down the cliff, making his way through the tarracks. He looks over his shoulder, sees me raise my head. The whole scene is red-lit from beneath, lending everything a surreal aspect, making me wonder if I really woke up at all.

'Orna! Do not move!'

Then my predicament really hits me. I turn my head a little and I see the cracks that radiated out from my body when I hit the surface. Even that slight shift in weight makes something crumble under my shoulders. Through the pain I can feel the tug and crunch of the river. This plate isn't going to last much longer.

Gingerly, I try to pick myself up. Something gives beneath me.

'Stay where you are!' Nereith cries, from where he's standing at the top of the cliff. 'He's coming to get you!'

But I'm being carried away from Feyn faster than he's descending, and anyway the heat is too much to stay still. There's a loud crack and my mind is made up. I push with my heels and elbows and roll to the side as the plate splits apart and a geyser of steam blasts into the air. The plate tips and bucks wildly; I cling to it with my fingernails, pressed face down. Burning hot shards of spume rock pepper my back and hair.

Gradually, the new plate evens out. It's holding.

I can't lie here for more than a moment; the heat is too much. I get to my feet. I'm not as careful or as delicate as I'd like, but I can't bear being spread flat on that surface any more. The rock tilts uneasily, but it holds.

I look back at Feyn, checking he's okay. Nereith has begun his climb now. The tarracks seem to have decided that we're not a threat as long as we stay away from the nests.

I begin to walk, spreading my weight. The far bank is just a slope, ragged with hardy lichen scrub. All I have to do is get to it.

The surface gives frighteningly with each footstep, letting me sink just a little. I'm light-headed; I can taste salt on my tongue. Dehydrating fast. I've got to move quick, but each time I put my weight down I'm convinced the plate is going to shatter and pitch me into the boiling sludge below.

The river is busy with rifts, moving apart and pushing together as the plates jostle for space. I have to jump them, even though the impact could crack the surface. The first is the most terrifying. I ride my landing down to one knee, absorbing it with my thigh muscles as best I can.

The plate stays firm.

Back on my feet, and I'm glancing up at the spike-rays, who are taking a worrying interest in these strange beings in their territory. I'm big prey for a spike-ray. There's no way one of them could lift me. But it might not stop them trying.

Feyn has reached the river, untroubled by the tarracks, and is beginning his crossing. I daren't think about him now. I have to concentrate on myself.

Over another rift, then out into the centre of the river, arms held to either side. I've got good balance, but the uncertain footing makes me want to simply run and hope for the best. The heat, the red glow from beneath, the protracted threat of imminent death – it's like being trapped in a nightmare.

Then I see one of the spike-rays begin a plunge. It comes down lazily but with purpose, heading for me, not caring whether I've spotted it or not. Almost nonchalant as it tries to kill me.

I tense, digging my toes into the treacherous crust. It'll come at me with the tail, in a stabbing motion; I watch as it curves, predicting the moment…

Now.

I jump aside and roll, clearing a rift with my jump, hitting the ground shoulder-first and coming up in a crouch. I finish the manoeuvre facing the spike-ray as it swoops back up into the sky, not in the least fazed by its lack of success. Then the ground shifts beneath me, and it's only because I'm in a ready stance that I move fast enough to avoid being cooked by a steam jet. Still, I land too heavily, and have to hop aside again for fear that the shattered ground beneath me will collapse like the last.

I can't stop myself hurrying now. I'm dizzy from the heat and I'm worried other spike-rays will follow their companion's example. The bank isn't far. A few solid-looking plates give me good landing spots, and I've got the measure of the tipping. Moving at reckless speed – although progress is still slow – I cover the second half of the river, buoyed by my own momentum.

The plates at the river's edge are a little more broken up, so I slow down again for them; but finally, with a last jump, my feet hit solid ground. I collapse amid the tough lichens, hugging the earth, and then scramble up the slope, away from the heat.

When the temperature is bearable again, I look back. Feyn is almost two thirds across, and by his face he's as frightened as I was. Nereith is behind him, making his way steadily. If we'd been carrying packs or wearing armour none of us would have stood a chance. Even the sword that Nereith wanted to take from the dead guard might have made a fatal difference. Suddenly I realise why this river makes such an effective moat for the fort.

But I've done it. I was right. I've got out, and I can get them out. As long as they don't stumble now…

I'm so fixed on watching Feyn that I don't see the spike-ray come for him until it's too late. It flies low over the surface of the river, and by the time I notice it I doubt my shout will help. But Feyn reacts fast to the warning, and with blind trust. Without even knowing where the danger is coming from, he throws himself forward. The spike-ray swings past him like an axe, its tail stabbing. Feyn arches his back with a yell as it scores across his ribs.

My hand goes to my mouth. He staggers forward, and for an instant I think he's going to fall, but then his head seems to clear. He checks for other spike-rays, and he's back on track again.

I don't take my eyes off him the rest of the way, demanding that he make it, as if by sheer force of will I can make his steps light and keep him from plunging in. Only when I see he's within reach of the shore do I allow myself a breath of relief.

I head downstream to meet him; he's been swept a little further by the current than I was.

I bundle him up the slope, my hands coming away red with blood. His thin shirt has been sliced through and there's a long lash across his ribs, but when I pull off his shirt and examine it, I realise it's not bad at all. Some blood, already dry in the heat, but little real damage. It'll heal as long as there's no poison.

'Does it burn?' I ask him, feeling around the wound for a barb that might have detached. 'How do you feel?'

'I feel weak,' he said. 'The heat…' He turns over so he's sitting on the slope of the riverbank, and in his expression I can read all the terror of the past few minutes. I have my chants, he has his philosophies, but in the end we're both the same and we're both scared rigid.

I kneel down next to him and put my arms around him, gathering his head into my collarbone. A moment later, I feel him return the hug, hard, as if clutching me is the only thing to stop him from being swept away. I can smell the bitter oil on his skin, feel his pulse through his forehead and wrists.

I miss my son. I miss him so badly.

'Hoy!' calls Nereith, and I hear him crunching up the riverbank from downriver. He crouches down next to us, panting, and grins. 'Where's my hug?'

I can't help laughing, because if I didn't I'd start to cry and I don't have time for that shit right now. Nereith is watching the spike-rays, but they've lost interest. We look back across the river, where Farakza glowers in the dark of the cavern, its shinehouse a beacon of pale light.

Nereith slaps me gently on the shoulder. 'Good job.'

A slow clang rings out from Farakza's bell tower, pulsing over us.

'End of shift,' I say quietly.

But the bell rings again, and again, and my heart and guts begin to squeeze tight. Not yet, not yet!

When Nereith speaks, he's saying what we all know. 'That's not the end of the shift,' he says. 'That's an alarm.'

17

Peering through the hide flap of the wagon I get my first glimpse of Farakza from the outside, as we bump and jolt away. The walls seem enormous from here, and though they're crumbling at the edges and battle-scarred, they don't look like they'll be coming down anytime soon. The fort crouches in the centre of its rocky island, solid and unadorned in contrast to the Gurtas' usual delicacy. It's built of the same black stone as the island, its interior buildings speckled with lighted windows.

The shinehouse at its centre is the highest point, casting the shadows of the watchtowers outward, splaying dark fingers across the island and the river beyond.

The Skein of Lament

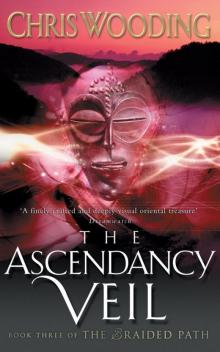

The Skein of Lament Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil

Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil The Ace of Skulls

The Ace of Skulls The Iron Jackal

The Iron Jackal The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray

The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil Storm Thief

Storm Thief Silver

Silver Pale

Pale Poison

Poison Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament

Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament The Ember Blade

The Ember Blade The Black Lung Captain

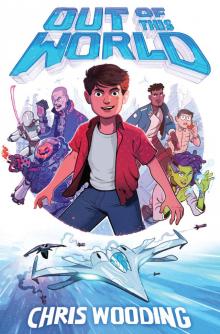

The Black Lung Captain Out of This World

Out of This World The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3

The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3 The Fade kj-2

The Fade kj-2 The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path

The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path Retribution Falls totkj-1

Retribution Falls totkj-1 The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls

Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls The Black Lung Captain totkj-2

The Black Lung Captain totkj-2 The Iron jackal totkj-3

The Iron jackal totkj-3 The Ace of Skulls totkj-4

The Ace of Skulls totkj-4 The ascendancy veil bp-3

The ascendancy veil bp-3