- Home

- Chris Wooding

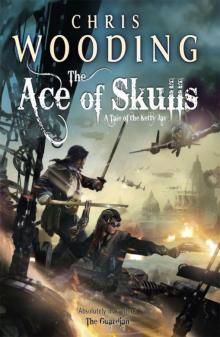

The Ace of Skulls totkj-4 Page 14

The Ace of Skulls totkj-4 Read online

Page 14

Ashua felt a pang of guilt. Crake had always been evasive about the exact nature of his guardian, but sometimes it seemed almost alive. A passing anger took her, that Crake would abandon his golem this way. She reminded herself that it wasn’t her problem.

She made her way to the nook between the pipes where she slept. She’d fashioned herself a cosy little spot there, lined with tarp and blankets, scattered with what meagre possessions she had. There was a fabric curtain for privacy. She liked her little den; in fact, she’d turned down the chance of a bunk for it. Having grown up sleeping on floors and in corners, she didn’t get on with beds. She enjoyed having the whole cargo hold as her domain instead of the cramped quarters upstairs. The pipes kept her warm at night, and soothed her with their creaking and tapping.

She rummaged through her bedding until she found what she was looking for. She’d hidden it away well between the pipes. She didn’t want anyone asking any questions. They wouldn’t understand.

She brought out the object that Bargo Ocken had given her back in Timberjack Falls, and studied it. It was a brass cube, small enough to sit in her hand. On the upper face was a button. On one of the adjacent faces was a small circular opening, covered with glass. That was all. An innocuous-looking thing, but an important one. With this, she could work her way to a small fortune.

She saw Bargo Ocken’s face as he sat across the table from her in a smoky bar. She heard his slow, measured voice. Look on us as, well, something on the side. Insurance. In case it all goes wrong somewhere down the line.

She began tapping the button on top of the cube. A code, a language she’d memorised long ago, created for just this purpose. With each touch, a light came on behind the glass circle on the side of the cube.

When she was finished, she waited. After a short while, it started blinking back at her.

Slag, the Ketty Jay’s moderately psychopathic cat, clambered out of the ventilation ducts and into the engine room. He was battered, scratched and bloodied, but he was triumphant. Another battle had been won deep in the guts of the aircraft, another blow struck in his lifelong war against the rats. It was all he’d ever known, this conflict. He was a warrior to the core.

The engine room was a noisy, rattling place full of machine smells. Neither the noise nor the stink bothered him: he was more at home here than he ever would be in a field or garden. The pipes and walkways that surrounded the huge engine assembly were Slag’s jungle. Right now he wanted somewhere to rest, somewhere that would put some heat into his ancient bones and tired muscles. He picked his way to his favourite spot atop a water pipe, tested the temperature and found it just right. There he settled to lick his wounds.

In days gone by the breeders in the depths had turned out monsters, huge rats to test his mettle. These were the challengers to his supremacy. The fights were vicious and terrible, but always he put them down. His many years of experience, his strength and speed told out in the end. He reddened his claws on the best of them.

This rat had not been the best of them. Big, yes, but nothing like the legendary enemies he’d defeated in his prime. And yet he’d struggled. He’d killed it, but he’d struggled.

Slag was an old cat. Tough as a chewed boot, but old. And of late he wasn’t as strong as he had been, nor as quick. He lived in a world of instinct and not reason, but even so, on some level he was dimly aware that his body was failing him.

The knowledge meant nothing. He could conceive of no other life but this one. His world was the Ketty Jay, its ducts and crawlspaces and pipes, and there he was a tyrant. He’d been beaten only once, by one of the huge two-legged entities that wandered around in the open spaces. The vile scrawny one had lured him away from his territory once, and defeated him there. But never on his own turf. Here, he was still supreme.

He lifted his head. A strange smell came to his nostrils, the merest whiff in amongst the acrid stench of aerium and prothane and oil. It was gone in a moment, but it was enough to put a suspicion in him. Ignoring the pain of his wounds and the aches in his joints, he dropped down from his perch and went prowling.

There it was again. He followed his nose, padding along metal walkways, up and down steps. It was no human smell that he knew, nor a smell of machines or rats. Soon he found a spot where it was strong, a particular corner he liked to spray on to mark his territory.

But there was a new scent there now, over the old. He sniffed. Something about it stirred a sense-memory from a time before the Ketty Jay, when he was only a squirming kitten in a litter. It took a few moments for everything to fall into place.

A cat. He was smelling another cat.

And it was on board the Ketty Jay.

Jez’s eyes opened. A crushing sense of loss settled on her. She was back on her bunk on the Ketty Jay.

How she dearly wanted that unconsciousness back. For that precious time, she’d been formless, drifting, and all around her had been music. The voices of her kin calling, their thoughts flashing everywhere, the great communication of the Manes. And in the darkness of non-thought she’d been with them, connected, and they’d welcomed her and begged their reluctant sibling to stay, stay, come and join them and be one of them for ever. She’d felt the enormity of belonging, and it was like a glowing coal in her heart.

But the memory was fading faster than a dream. She was back in the world, back in that place of limited senses and limited desires. Back to the drab, cold torpor of isolation.

‘You hear them, don’t you?’

Pelaru’s voice made her turn her head sharply. He was sitting in the dark by her bunk. She felt a flood of nervous joy at seeing him there, washing away the sadness.

‘Yes,’ she said. Her tongue felt unfamiliar. She had trouble shaping the word. It was sometimes like this, when she returned. It got harder and harder to remember how to be human.

Pelaru shifted himself. He seemed discomfited. ‘Osger heard them. All the time, he said. Tempting him. Drawing him away from me. Sometimes he. .’ The Thacian’s voice drifted off. ‘What is it like, to be so close to them?’

‘It’s. . wonderful,’ she said. His expression tightened, and she knew she’d said the wrong thing. But she couldn’t lie.

‘Do you think he’s with them now?’

‘I don’t know.’

Her eyes roamed over his face in the dark. His grief suited him, made him seem nobler; but she longed to see him smile.

‘He was always. . torn,’ said Pelaru, and then he did smile, but not in the way she’d wanted. A bitter smile, recognising the irony of what he had said. Osger had ended up in two halves. ‘I could never understand. Why would you give yourself up that way? Give up your humanity? To be one of them?’

He spoke the last word with such hatred that Jez almost feared to answer. How could he love a half-Mane and yet despise them so? ‘It’s not like giving yourself up,’ she said at last. ‘It’s like opening yourself up.’

‘By turning yourself into a horror,’ Pelaru sneered, and the disgust in his voice wounded her.

She sat up in bed. She was fully clothed, still covered in stone dust, her overalls torn at the arms and legs. She looked a mess, but she didn’t care. ‘Is that what you think I am?’ she asked. ‘A horror?’

‘No,’ he said. ‘No, and that’s the worst of it. I. . feel for you, Jez. From the first moment I saw you, I felt something. Something as strong as that which I felt for Osger. Even seeing you that way, back in the shrine. . as a Mane. It doesn’t change a thing.’

A sensation both hot and cold and blessed spread through her, like the touch of some benevolent deity. She tried to make herself speak, but found that it was hard, although for different reasons than before.

‘I. . I feel that too,’ she said clumsily.

Agitated, he flung himself to his feet. ‘What is it?’ she asked, fearing that she’d done something wrong, that she’d repelled him. How was she supposed to act? She’d never done this before, never anything like this.

‘This shoul

dn’t be,’ he said, his voice thick. ‘Osger is not a day dead in my mind and yet. .’ He clenched his fists. ‘This shouldn’t be!’ he said again, angrily. Then he walked out of Jez’s quarters, and slid the door shut behind him.

Jez was left sitting on her bunk, the joy of a moment ago withering to an ashy despair.

‘Why not?’ she asked the darkness, quietly.

Thirteen

Arrival — A Welcoming Committee — The Prognosticator — Ashua Gets Creative — The Allsoul Speaks

The sun was breaking over the horizon when they reached the Barabac Delta. Strawberry light cut low across a colossal mangrove swamp that stretched from horizon to horizon. Frey rubbed tired eyes and gazed out over the endless expanse before him. Bayous and mighty rivers cut channels through the greenery, glistening in the dawn light. Hills rose steep and sharp from the watery murk, shagged with tropical trees. Vardia was a land so enormous that the weather from one end to another differed drastically. Here on the south coast, not far from the Feldspar Islands, the chill of winter was never felt.

It had taken them a day and a night to get here. Frey had reached the first rendezvous in the early afternoon, well ahead of the slower craft in the fleet. He’d landed the Ketty Jay in a mountain valley and caught up on some long overdue sleep while the rest of the Awakeners gathered. When night fell, Silo woke him and they took off again. There was another round of identity checks, for which Abley’s assistance was needed once more, and then they all headed south en masse, without lights.

It was a dangerous business, night-flying with an undisciplined mix of volunteers and conscripts. Most of them had never flown in formation in their lives, and certainly not in the dark. Even though they kept very loose, with plenty of distance between each aircraft, there were a few accidents. All of them were fatal. Wonder if their all-seeing Allsoul saw that coming? Frey thought uncharitably.

As they flew, Frey had begun to hope. He was heading towards Trinica at last. The thought energised him, and anticipation made the long night flight bearable.

He knew he’d put his crew through a lot. He knew he should have told them what he was up to in the first place. But he happened to think he’d been doing a pretty fine job of treading the line between what his crew wanted and what he wanted. Maybe Malvery and Crake had issues about the war, but everyone else wanted to stay well out of it. Maybe some of the crew didn’t think Trinica was worth risking their lives for, but they’d risked their lives for Frey on plenty of other occasions, so why was this different? And he was making sure they all got paid: there was a pile of Awakener treasure in the hold that Pelaru had forfeited as part of their deal, plus everything they’d nabbed from the shrine beneath Korrene.

He still wasn’t sure if they were chasing phantoms. He still wasn’t sure if Trinica would even see him, if he ever managed to track her down.

But he had to try. It was as simple as that.

During that long flight he thought of Crake as well. Frey hoped he was alright. He hoped he’d make contact again, sometime soon. He hoped a lot of things, but they were all out of his hands now. Crake had gone, and while Frey felt guilty, he didn’t entirely blame himself. It had been one moment of thoughtlessness that had driven his friend away. If Frey beat himself up every time he did something thoughtless, he’d be in a wheelchair.

It occurred to him belatedly that they still had Pelaru aboard. But the whispermonger had shown no signs of wanting to leave, and Frey hadn’t had the opportunity to drop him off anywhere. As long as he kept quiet, Frey didn’t mind overmuch. Information being his business, he might even turn out to be useful.

Once they were over the swamps, the fleet dropped down low to follow a river. The bigger craft travelled in single file while the fighters buzzed around them. Though much of the land was submerged, there were many islands and bluffs, and the trees grew high and thick. In this terrain, and with anti-aircraft batteries supposedly concealed everywhere, it was no wonder the Coalition had been having trouble tracking down the Awakeners.

You could search for ever and never find someone in this place, Frey thought. Which, he reminded himself, was entirely the point.

The heat began to grow as the sun rose higher in the sky. Brightly coloured birds winged across the convoy’s path. Twisted trees spread roots like hag’s claws into the torpid water. Reptiles slid between them, half-submerged.

The river branched and branched again, and finally it came to a kind of open-ended valley between two island peaks that thrust out of the waterlogged earth. Then they rose up, over the trees, and below them Frey saw their destination.

The base, such as it was, spread over kloms of swampland. Dozens of clearings, some natural and some man-made, were hidden between the trees. Thousands of aircraft ranging from tiny to mid-sized stood in them, raggedy old crop-dusters and sleek pleasure craft alike, all getting kitted out for war. Anti-aircraft guns lurked nearby, watching the sky.

A small makeshift town had been constructed in one of the largest clearings near the centre. Ramshackle huts had been built and large tents put up. Most of the people seemed to be there, Frey noted as they flew over it. Presumably that was where they distributed supplies and information.

Frey hadn’t expected much, but he still thought it was a dump. The Awakeners didn’t have half the resources and organisation the Coalition did. He couldn’t imagine how they hoped to win, the way things stood.

Well, at least the ground was above water level, he thought, as the fleet leader signalled and the craft began to land. Frey looked for the Delirium Trigger, but there was nowhere nearby to hide such a massive craft. That worried him slightly, but he wasn’t to be deterred. He’d simply make his way to the town and ask around.

He brought the Ketty Jay down in a small clearing shared by a couple of freighters that looked like they’d been assembled from junkyard scraps and cutlery. He powered down the engines and flopped back in his seat in relief.

Trinica, he thought. Here I am at last.

‘Trouble, Cap’n,’ Silo called down the corridor from the cockpit.

Rot and damnation, what now? Frey thought. He’d been staring critically at himself in the grubby mirror above the metal sink in his quarters. There were heavy bags under his eyes. He’d only snatched a few hours’ sleep since they set off for Korrene the day before yesterday. After flying all night, he looked fit for the knacker’s yard. Not the face he wanted to present to his long-lost love.

He tore himself away from the mirror — even at his worst, he found a ghoulish fascination in his own reflection — and went to see what the matter was. He found Ashua dragging Abley up the corridor at gunpoint. His hands were tied before him with rope.

‘I warned you, didn’t I?’ she told him. ‘Cap’n, where can we shoot this little bastard where he’ll make the least mess?’

‘Whoa, whoa! Don’t anyone shoot anyone till someone tells me what we’re shooting people about,’ said Frey.

Ashua pulled the terrified Abley to a halt, and pressed a pistol to the side of his head. ‘There’s a bunch of armed Awakeners out there, that’s what. And they want to come in. I call that quite a bloody coincidence, don’t you?’

‘Where’s Harkins and Pinn?’

‘Here! Here!’ Harkins said, stumbling out of his quarters in his long johns, with the imprint of a pillow stamped into one side of his face. ‘Thought I’d catch some sleep. Er, it was quite a long flight. Sorry, Cap’n.’

‘And Pinn?’

From the door behind Harkins, there came an intake of breath as if someone were cranking up a ballista, followed by a despairing wheeze like the lamentations of the damned.

‘Is he snoring or dying in there?’ Frey asked.

‘Er. . well. . when he’s asleep, it takes a bomb to wake him,’ Harkins said. Then he dropped his voice, glanced back through the door and covered one side of his mouth. ‘It’s probably because he’s an enormous lazy turd,’ he added bravely.

Well, that put paid to the id

ea of flying off. He wasn’t going to leave the Skylance and Firecrow behind.

Silo came out of the cockpit and into the corridor. ‘They lookin’ pretty impatient, Cap’n,’ he advised.

Frey was beginning to feel flustered. First bags under his eyes, and now this? ‘Where’s the doc, then?’

‘He won’t be getting up, Cap’n,’ said Jez, who’d appeared out of her quarters. ‘He was drinking pretty hard yesterday.’

Frey was glad to see her up and about. She’d put on new overalls and washed, and she looked more focused than he’d seen her in a while. That, at least, was heartening.

He made a quick decision. ‘We’ll have a pretty hard time explaining away a dead man if they come aboard,’ he told Ashua. ‘Bring him. Silo, you too.’

He headed into the infirmary. Ashua pushed the prisoner along after and Silo followed. Frey picked his way through Malvery’s medicine cabinet until he found a bottle with the right label. ‘Hold him still,’ he said absently.

‘I didn’t tell them! I swear! I did what you said!’ Abley was wailing, as Silo wrapped strong arms round him to secure him.

Frey found a wadded rag, tipped some of the bottle on it, and then slapped it over Abley’s nose and mouth. ‘That’s enough out of you,’ he said.

Abley struggled for a moment, but not hard enough to break Silo’s hold. His eyelids fluttered as he breathed in the chloroform, and then he went limp.

‘Give me a hand,’ he told Silo. Between them, they hauled Abley to the operating table and left him there.

‘If he’s shopped us, Cap’n, I’m coming back to shoot him, unconscious or not,’ Ashua promised.

There was a banging on the cargo hold door, faintly heard. Frey straightened, arranged his hair a bit, and went back out into the corridor. ‘Ashua, Silo, come with me. Jez, find Pelaru, make sure he stays quiet. I don’t trust him not to sell us out. Harkins. .’ He waved at the air, unable to think of anything useful that Harkins could possibly contribute. ‘I don’t know, get dressed or something.’

The Skein of Lament

The Skein of Lament Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil

Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil The Ace of Skulls

The Ace of Skulls The Iron Jackal

The Iron Jackal The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray

The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil Storm Thief

Storm Thief Silver

Silver Pale

Pale Poison

Poison Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament

Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament The Ember Blade

The Ember Blade The Black Lung Captain

The Black Lung Captain Out of This World

Out of This World The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3

The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3 The Fade kj-2

The Fade kj-2 The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path

The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path Retribution Falls totkj-1

Retribution Falls totkj-1 The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls

Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls The Black Lung Captain totkj-2

The Black Lung Captain totkj-2 The Iron jackal totkj-3

The Iron jackal totkj-3 The Ace of Skulls totkj-4

The Ace of Skulls totkj-4 The ascendancy veil bp-3

The ascendancy veil bp-3