- Home

- Chris Wooding

The Ember Blade Page 5

The Ember Blade Read online

Page 5

‘I doubt they even exist,’ said Master Fassen. ‘A secret underground network? I say it’s wishful thinking on the part of those who’d see us gone.’ His brows gathered together. ‘Though Salt Fork is somewhat concerning, I will allow. These rebels grow bold.’

Randill wiped his mouth and sat back. His face was all angles, hard and spare of flesh, but it softened when he smiled, and he smiled often. Aren had inherited his dominant nose and wide jaw, but his gentle eyes and fuller mouth came from his mother.

‘Greycloaks or not, they were rebels of some stripe. My poor luck that we were close to Salt Fork when the trouble hit. I’d found an opportunity, some land I thought would make for good vineyards. We were coming to a deal when Salt Fork was seized, trade snarled up and the army came through. There was no business to be done with anyone after that.’

‘But you were so late returning.’ Aren tried not to make it sound like a complaint, but it came out like one. He couldn’t help it. It wasn’t his place to question his father, but he was disappointed that there’d been no letter, no word of explanation until now.

‘My travel permit only allows me to use certain routes, and in avoiding the chaos round Salt Fork, we strayed too far and fell foul of a particularly … diligent official.’

Kuhn stopped eating pies and cheese for long enough to give a snort of disgust. Aren noted he avoided the fruit like it was poison. He was a squat, shaggy man, dark-haired and weatherbeaten, who hunkered jealously over his food as if defending it from potential thieves.

Randill gave him a faint smile. ‘This particular paragon of efficiency kept us locked up until we could send word to the right people and get ourselves released.’

‘They locked you up?’ Aren was appalled. Now he felt guilty for mentioning it. No wonder there had been no letter!

Randill shrugged. ‘He was just doing his job, I suppose.’

‘Scribes and clerics,’ Kuhn grunted. ‘That’s what’s wrong with the world now. Time was you could ride from Ossia to the lowland coast and you didn’t need a piece of paper to do it. Once, arguments were won with blades and bravery. Now it’s who tells the finest lies in a courtroom. Used to be a man’s oath was enough for truth, but honour’s long gone, and we put contracts in its place.’

‘Here, now!’ said Master Orik. ‘You Brunlanders needed some organisation. You barely knew how to lay a decent road before we came!’

Randill slapped a hand on Kuhn’s shoulder, intercepting him before he could rise to it. ‘Forgive my friend, Master Orik,’ he said. ‘It’s the curse of Brunlanders to speak plainly.’

‘True,’ said Kuhn resentfully. ‘We never did learn the trick of keeping our mouths shut so as not to discomfit our masters.’

There was an awkward silence in which Randill gave Kuhn a hard stare. The Brunlander held it as long as he dared, then looked down at his plate.

‘Anyway,’ said Randill, once satisfied that his authority had been asserted, ‘Salt Fork is over, the rebellion put down. Let us be glad of that.’

Aren was glad of it indeed. It had made him uneasy to see the suppressed excitement on the faces of his countrymen when they spoke of Salt Fork and the Greycloaks. Their appetite for treason angered him. But he saw now that he need not have worried; it was an empty dream they entertained. They wished for revolution, but they weren’t willing to inconvenience themselves to get it. They wanted someone else to shed the blood for them.

‘Tell me what I’ve missed,’ said Randill, in an effort to restart the conversation and restore some levity to the room.

‘Aren just beat Master Fassen at castles,’ Nanny Alsa said, with a mischievous glance at Aren.

‘Is that so?’ Randill cried, delighted. ‘And I thought the old twig was unbeatable!’

Master Fassen bristled and smoothed his sideburns with his knuckles. ‘Old twig!’ he muttered.

‘How did you do it?’ Randill asked Aren.

‘I owe the victory to Master Orik, actually,’ said Aren. Master Orik looked up from his brandy glass in surprise. ‘“To overcome your enemy, you must first understand him.”’

‘Ah, yes,’ said Master Orik, though he still seemed bewildered to be getting the credit. ‘That’s so.’

‘A strange idea to teach a boy learning the sword,’ said Master Fassen, ‘when his only goal is to spear the object of his attention with a length of polished steel.’ His tone made it clear what he thought of the fighting arts.

‘Not at all!’ said Master Orik. ‘If you see only the enemy, you do not see the man. People are more than just enemies and friends, opponents and allies. Does he hate you? Then he may reach too far, swing too hard. Does he fight to defend his family? Then he may be careful, or desperate. Does he seek death, or fear it? Know his heart and your blade will find it all the easier.’

‘I presume you didn’t beat Master Fassen by stabbing him through the heart, though?’ Randill said to Aren. ‘That would be a cheap victory.’

‘I should think he didn’t!’ Master Fassen spluttered. He was beginning to feel picked on, and it was hard on his dignity.

‘Master Fassen scorns the weak mind and despises the lazy and inattentive,’ Aren explained. ‘I threw the last three games to persuade him I was both.’ He knew he shouldn’t go on, but he was unable to resist. ‘Eventually it made him lazy and inattentive himself.’

‘Well, that’s too much!’ Master Fassen exclaimed, red-faced. Randill roared with laughter, Master Orik choked on his cheroot and even Nanny Alsa had to hide a smile.

‘You’ve got your mother’s gift,’ Randill told him. ‘She could see right through people, knew what made them tick. One look at someone and she had them figured out.’

‘Would that he applied half so much craft to his studies,’ grumbled Master Fassen.

While they’d been talking, a servant had slipped into the hall to stand by Randill’s chair. Now he leaned down and whispered in Randill’s ear.

‘Of course. Send them in,’ said Randill.

The servant motioned to the doorway, where the cook and one of his boys were lurking. They came to stand before the table, beneath the portrait of the Imperial Family. The boy, a mop-haired youth with a large brown birthmark on his cheek, looked nervous.

‘Apologies for interruptin’,’ said the cook, ‘but the boy has something I think you’ll want to hear. Tell ’em what you told me, Mott.’

‘I been to town for bacon,’ Mott blurted. ‘I was in the square, and a rider comes thunderin’ in, all done up in fancy livery. Says he’s an Imperial messenger, says they’ve been sent far and wide to announce the good news!’

He stopped breathlessly, anxiously awaiting a reaction. The cook clipped him round the ear. ‘Which is …?’

Mott’s face cleared as he realised he hadn’t actually told them the good news yet. ‘He says there’s to be a royal marriage! Prince Ottico is marryin’ Princess Sorrel of Harrow less than five months hence, on the last day of Copperleaf, um, I mean Deithus,’ he added, belatedly remembering to use Krodan months instead of Ossian.

‘Hurrah!’ cried Master Orik, surging from his seat. ‘I’ll drink to that!’ He held his brandy glass aloft, waiting for the others to join him.

Nanny Alsa clapped her hands. ‘What wonderful news!’ she declared.

‘And that ain’t all!’ Mott went on. ‘As his weddin’ gift, Prince Ottico’s to be made Lord Protector of Ossia! The Emperor’s givin’ him the Ember Blade! Thirty years it’s been gone, but the Ember Blade’s comin’ back to Ossia!’

Aren straightened in his chair. All his life he’d scoffed at the tales and superstitions that surrounded the Ember Blade, yet the thought of it still rang some distant chord in his soul. That sword was the symbol of Ossia itself; he couldn’t help but feel its significance.

‘Has it been thirty years?’ Randill asked faintly. His eyes were distant; the news had struck him as it had his son. ‘Yes, yes, you’re right. Thirty years since Queen Alissandra fell. How the years have

flown.’

‘Thirty years,’ said Kuhn grimly. ‘And now the Ember Blade comes back in the hands of a Krodan.’

‘That’s enough, Kuhn,’ said Randill. He sounded weary and sad. ‘That’s enough.’

He got to his feet. Master Orik was still standing with his glass held aloft, arm trembling, unable to drink or to sit down without a humiliating loss of face. Randill raised his goblet. It was the signal for the others to rise and do the same; all but Kuhn, who remained resolutely seated.

‘To the royal marriage,’ Randill said, and they drank. Master Orik gulped his brandy down with obvious relief. ‘Now, you’ll have to excuse me. I’m tired from the ride and a hot bath is calling.’

They said their goodbyes and he walked from the room, ruffling Aren’s hair distractedly as he passed. Aren watched him go, a concerned frown on his face.

Master Orik poured another slug of brandy into his glass and raised it again, tottering only a little as he did so.

‘To the health of our good Prince Ottico!’ he slurred.

‘Oh, sit down, man!’ snapped Master Fassen.

8

After his bath, Randill retreated to his study and his papers. Aren went to find him there, bearing a tray with two crystal glasses and a silver jug of golden sweetwine.

He entered quietly so as not to disturb his father’s thoughts. The study was full of cosy shadows cast by candles and wall-mounted lamps. Unshuttered windows let in the sea breeze; thin curtains stirred beside a desk piled with documents. There were shelves containing maps and records and a few valuable hidebound tomes, and on one wall hung the symbol of the Sanctorum in brass and gold: a downward-facing sword resting across an open book, its pages like wings to either side of the blade.

Randill sat in a wooden armchair of Krodan design, its high, straight back decorated with bold symmetrical rays. He was leaning forwards with his elbows resting on his knees and his hands clasped, staring intently into the darkness of an unlit hearth. Several letters lay open on a side table.

Aren watched him from the doorway. Perhaps it was the vacant chair at his side, or his pensive manner, but his father cut a haunted figure tonight. Randill had still not noticed him, which Aren thought strange. It was normally all too easy to break his concentration, and the servants knew to be stealthy when he was working. He showed no sign of stirring, so Aren walked across the study, carrying the tray before him. ‘Father? I brought you—’

Randill jerked violently at the sound of his voice, then lunged out of his seat towards Aren, fear and hate in his eyes. Aren went rigid with shock. Halfway to his feet, Randill checked his attack; Aren saw recognition dawn on him, and his face crumpled as he sank back in his seat. Aren’s gaze switched to the letter knife in his left hand, which he’d snatched up to plunge into his son.

‘Father?’ Aren said tremulously. He was still holding the tray level. The dainty crystal glasses had wobbled but not tipped.

Randill pinched the bridge of his nose and closed his eyes. ‘Forgive me,’ he said. ‘You startled me.’

Aren’s mind was blank. For an instant, he’d seen a cornered man, mad and desperate. Now his father looked weary beyond his years.

‘I brought some sweetwine,’ Aren said, dully. ‘It’s Amberlyne.’

‘Thank you,’ said Randill. Aren placed the tray on the table and retreated in confusion, but Randill caught his arm in a gentle grip.

‘Sit with me awhile, my son,’ he said. ‘We’ve been long apart, and I’ve missed you.’

Randill’s voice calmed him a little. There was the man he knew. Still wary, he drew up another chair as Randill poured the wine.

‘Who did you think I was?’ Aren asked. The words came out unbidden, but he had to know.

Randill gave him a wry smile. ‘Perhaps I thought you were the Hollow Man.’ He handed one glass to Aren. ‘You remember him, don’t you?’

Aren remembered him well. It was difficult to forget the nightmares he’d suffered as a young boy on the Hollow Man’s account. But that was just a tale to scare children, and it angered him that his father would try to palm him off with such fictions. He took a glass and stared at it resentfully.

Randill saw it and sighed. ‘I don’t know who I thought you were,’ he said. ‘For a moment, you seemed an enemy. A robber, perhaps. I am more tired than I thought.’

Aren was reluctantly content with that. He glanced down at the letters on the table and wondered if they were the cause of his father’s upsetting behaviour, but enquiring into his private mail would be to pry too far.

Randill raised his glass in salute, and they sipped. The complex, delicate taste of Amberlyne flowed over Aren’s tongue, now sweet and nutty, now creamy, now sharp. Randill let out a breath of satisfaction and Aren relaxed a little more.

‘There truly is no wine like Amberlyne,’ said Randill, admiring the contents of his glass in the lamplight. ‘One thing our people can still sing about.’ He looked over at Aren. ‘Soon you’ll be the one travelling, eh? Your military service.’

‘I’m ready for it, Father,’ Aren said.

Randill chuckled. ‘I’ve no doubt you are. Master Orik tells me you’ve been working hard, and that what you lack in natural talent you make up for in persistence. Your other tutors tell me the same. They say there’s no student more dogged than you.’

‘You’re being kind, Father. I know what they say. I try my best, but the lessons don’t seem to stick.’

‘Well I know that pain,’ he said. ‘I was the same. No boy was beaten more often than I.’ He grinned, and Aren grinned back, warmed by the wine. ‘I gave up on my schooling, chose the life of the blade instead. Likely I’d have died of it if I hadn’t inherited our family’s lands. Not you, though. You keep going. You force yourself onwards, no matter how unpleasant the task.’

‘There is no great honour in working hard for what you want,’ Aren said modestly, deflecting the praise as Krodan etiquette dictated. ‘The Primus teaches us that. Diligence and persistence bring all things to a man.’

‘So they say,’ Randill replied, but his smile became strained and fell away. ‘Would that the world were as simple as priests see it.’

‘Father …’ Aren hesitated, afraid to ask the question, afraid of an answer he wouldn’t like. ‘The wedding … I saw how it affected you. Aren’t you glad?’

‘Glad enough,’ said Randill. ‘It’s a canny match. Our nervous neighbours to the north have a formidable army and grave concerns that they might be the next country swallowed up by the Third Empire. A match between the last two royal families on the continent will stabilise the region and present a united front against Durn. They executed their own royal family not ten years past, and neither Harrow nor Kroda want anyone getting any ideas.’

‘But …?’ Aren prompted.

‘Ah, my son. Fifty-five years I’ve been alive, you know. I’ve lived longer with Krodans as our rulers than without. But for twenty-five years I had the freedom to go where I pleased. The Nine held sway over this land, and we all spoke Ossian and nothing else. I saw the reigns of two queens and a king in that time, but only ever one Ember Blade. A sword of rarest embrium that showed red like fire in the rays of the sun. You know they named Embria after the Ember Blade? Did they teach you that in school?’

‘They did, Father.’

‘It’s more than a sword. There’s something of the divine in it. We believed it was a sign of approval from Joha himself. Every Ossian ruler since the Reclamation had it in hand when they took the throne, and whoever held it was meant to rule. Even in our darkest days, when we had tyrant kings, or weak ones, or mad … Even then, people believed that the Ember Blade would find its way to the right hands, guided by the will of the Aspects. We didn’t know it, I think, but all our faith was in that sword. Our dreams for what we might one day become as a people. It was the last piece of the old empire that wasn’t crumbling, or forgotten, or dead.’

Aren had never heard his father speak this way before. He’d

always been guarded when discussing the past, careful not to say anything unfavourable towards the Krodan regime. The passion and longing in his voice made Aren uneasy, but they also made him understand.

‘And now it returns to Ossia in the hands of a Krodan,’ Aren said, echoing Kuhn’s words at the dinner table.

‘We’ve lived well these thirty years,’ said Randill. ‘Life has been good under the Krodans. But it’s still hard news to bear. I’d thought it locked in some dusty vault, or on display in the Emperor’s palace in Falconsreach, far from here. I’d thought never to hear of it again.’

‘Perhaps …’ Aren ventured. ‘Perhaps it has found its way into the right hands. After all the turmoil of the Age of Kings, perhaps this is the stability Ossia desires. Perhaps Prince Ottico is meant to rule?’

‘Ha!’ Randill’s laugh was humourless. ‘If the Nine really guide its destiny, I doubt they’d place it in Krodan hands. Not while the Sanctorum starves their temples of funds, arrests their druids, makes mock of their teachings and all but outlaws them entirely.’

‘Father …’ Aren warned. This was getting too close to sedition.

Randill held up a hand in apology. ‘Forgive me,’ he said. ‘I suppose the old gods are no easier to cast aside than the Ember Blade was, much as we might try. We learn the world in our youth and believe that is how things are. To unlearn it … Well, I wonder if we ever really do. And, sometimes, if we should.’

‘What happened, Father? When the Krodans invaded. Did you fight them?’

‘I did,’ he said, bowing his head. ‘We all did, for a time. Until the Ember Blade was lost.’

‘And then?’

‘Then I compromised,’ he said. ‘It was that or die.’ He looked across the table. ‘Do you recall the day you came to me and asked me to take on Master Fassen? You said you needed extra lessons to keep up with the other boys.’

The Skein of Lament

The Skein of Lament Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil

Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil The Ace of Skulls

The Ace of Skulls The Iron Jackal

The Iron Jackal The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray

The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil Storm Thief

Storm Thief Silver

Silver Pale

Pale Poison

Poison Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament

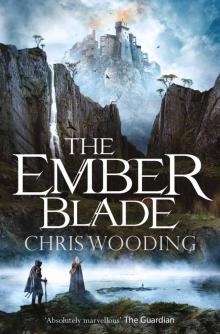

Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament The Ember Blade

The Ember Blade The Black Lung Captain

The Black Lung Captain Out of This World

Out of This World The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3

The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3 The Fade kj-2

The Fade kj-2 The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path

The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path Retribution Falls totkj-1

Retribution Falls totkj-1 The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls

Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls The Black Lung Captain totkj-2

The Black Lung Captain totkj-2 The Iron jackal totkj-3

The Iron jackal totkj-3 The Ace of Skulls totkj-4

The Ace of Skulls totkj-4 The ascendancy veil bp-3

The ascendancy veil bp-3