- Home

- Chris Wooding

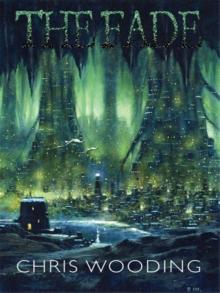

The Fade kj-2 Page 6

The Fade kj-2 Read online

Page 6

He could have had me executed, but then questions might be asked, and he doesn't want those kind of questions. He could have sent his Cadre: at least they might have done the job right. But then, he couldn't take the risk that I'd beat them, and then I'd know what he was up to.

But I know, Ledo. I know.

The last assassin makes his move. I take the fight to him. It doesn't last long.

7

I need to be active. Sitting in that graveyard of a home is killing me. So I send out a message to an old friend, and while I'm waiting for it to find him, I fulfil a promise I made to a dead man.

Spikevine hangovers are not the most pleasant of experiences, but I've invited the pain in and now I have to suffer it. Punishment for failure, and for my stupidity. Mouth dry and sticky, joints aching, I head into the seedier districts of Veya to deliver the letter entrusted to me by Juth before our escape from Farakza.

The address is in the Scornhold, on the poleways side of the city, just neath-backspin of the Flay and turnward of Marasca Springs. It's a run-down area in the process of revitalisation, all narrow, crumbling alleyways and graffiti. Far from the shinehouses that tower over the city, dimmer than the more wealthy areas. Lantern-posts dot the streets, some lit, some dark. Corners and alcoves are guarded by small groups of dangerously idle young men, eyeing passers-by.

I'm safe enough. Usually the Cadre symbol skinmarked on my shoulder is enough to deter anyone, but sometimes the thought of taking down a Cadre woman is too tempting. Thing is, anyone idiotic enough to try random violence against Cadre is almost certainly going to die for their trouble. Smart fighters, disciplined fighters, don't hang out on street corners desperate for someone to threaten in order to prove their masculinity. They're not that insecure.

The air rings with the blunt din of construction, adding to my already spectacular headache. Dirty arcades bristle with rootwood scaffolding and counterweighted crane jibs. Eskarans and Craggens work side-by-side here, the latter hauling great sleds of rock or applying their immense strength to huge pulleys. The air is dense with their language: a breathy, explosive mixture of glottal stops, swallowing noises and booming sounds. They hulk their way among their smaller companions, flat, spiked tails dragging behind them.

I've always had a bit of an affinity for Craggens. There's something alluring in their way of thinking, their lazy, gentle myths and simple yearnings. They don't hurry anywhere, and they seem unaffected by ambition or the traumatic complications of life.

As I watch them, I wonder what really goes on in the minds of these massive humanoids, with their small, tusked snouts and tiny black eyes. They're built to be unstoppable warriors: shambling mountains of red hide armour with a shaggy mane of quills running down their backs. But instead they're content to live their own slow lives, deep in the earth, where the pressure and heat is too great for us to follow.

It's a good system we've got, us and them. The males work in Veya to raise the money to build luxurious dens to attract females, who have to come nearer the surface to give birth. The young are more fragile than the adults. Eskaran craftsmen make the dens, which are far more elegant than Craggens can construct with their massive hands. The more elaborate the den, the more likely the male is to score a female.

When Craggens and Eskarans first came into contact, there wasn't a war. We just made a deal. Would that every meeting of cultures was so easy.

The address on Juth's envelope takes me down a dingy stairway, below street level, to an iron door with a viewing-slot. I hammer on it. Footsteps approach, and the shield on the slot slides back.

'What?' demands the girl on the other side. She's probably eighteen, twenty at most. Garish make-up, colourfully dyed hair. High cheekbones and bluish skin, giving away her Yurla bloodline.

'I've got a letter for you,' I say. 'From Juth.'

Surprise in her reaction. Then suspicion. 'So where is it?'

I hold it up.

'Put it through.'

I shove it through the slot, and she pulls the shield closed. I wait for a few moments, nonplussed, and then decide I can't be bothered with this and go back up the stairs. Promise fulfilled. I don't even really care what was in the letter.

I'm some way down the street when the girl comes running after me, followed by a dreadlocked scruff in his late twenties. 'Hoy! Hold up!' he shouts.

I stop and stare at them expectantly as they come to a halt in front of me. The man has the letter in his hand, now open.

'You knew Juth?' he asks, panting. It was only a short run. He might be wiry, but he's unfit and he smokes too much.

''Not well,' I say. 'He asked me to deliver that for him.'

'You were in a Gurta prison?'

'Farakza. Juth is still there.' I feel like doing something pointlessly vicious so I say: 'He's probably dead by now.'

It doesn't appear to bother them at all. The girl notes the Cadre sigil on my exposed shoulder for the first time, and she nudges the man with a pitiful lack of subtlety.

'You're Cadre?' he asks. He's nervous.

'That's right,' I say. 'And you two work for the Undercity Press, distributing subversive and illegal literature throughout Veya. You also have offices in Vect and Bry Athka and Lera, who handle distribution in those cities.' I look at the man steadily, whose jaw has dropped. 'I don't know who she is, but I'm guessing that you're Cherita Fal Barlan, the editor?'

He freezes up, guilt all over him. The girl looks like she's ready to run.

'Recognised the address,' I say, motioning at the envelope.

'You knew where we were?' Barlan gapes. 'How long?'

'Couple of years. Just never had cause to visit you.'

Still stunned. Doesn't know where to go next. I put him out of his misery.

'Listen, it's my business to know this stuff. You're not as secret as you'd like to believe. I'm sure you're wondering why Clan Caracassa haven't raided your premises and had you all arrested long ago, right?'

'Uh… it had crossed my mind,' he says. 'We publish some… pretty unfavourable books about the Plutarchs.'

'You want the truth?' I say, pinching the bridge of my nose, where my headache is sharpest. 'Nobody cares. The Plutarchs have bigger things to worry about. So do I.'

'Nobody cares?' the girl repeats, aghast.

'You're not half the thorn in the establishment's side that you think you are,' I tell her. I'm not in the mood to coddle anyone right now.

'Shit, that's a comedown,' says Barlan, deflating. 'Think I'd rather be arrested than ignored.'

'I can break your legs if you like. Would that make you feel better?'

It takes him a moment before he realises I'm not serious. He smiles uncertainly, then looks from me to the letter in his hand. 'You wanna come see?' he offers.

'Barlan!' the girl cries.

'She already knows, Pela,' he says. 'Besides, Juth trusted her.' He looks back at me. 'So? I'd like to talk to you.'

I have time to kill, and the old information-gathering instincts are still sharp. I motion to him to lead on.

Barlan hands me the letter from Juth and tells me I might as well read it, after all I went through to get it here. We head back to the stairs and through the iron door, into a short mould-speckled corridor that opens into a dim room cluttered with bales of broadsheets and boxes of books. Against one wall is a hand-cranked printing press. Two other men sit at makeshift desks, one reading mail, one scribbling furiously. Like Pela and Barlan, they're dressed scruffily, trying a little too hard to be malcontents. They react to my presence first with interest, then with alarm.

While Barlan is arguing with them I read the letter. It's short and to the point. If this letter reaches you by some other hand, it is because I could not bring it myself and am likely dead. The bearer of this letter has escaped from Farakza, a Gurta prison where I am being held. Fortune took one masterpiece from my hands, but it may yet provide another. Stop at nothing to get the story from this person. We will show the people what thei

r sons can expect if they are unlucky enough to face capture in our 'glorious' war. Consider it my final commission. Juth.

'Yeah, sorry about him,' says Barlan, as I fold up the letter and give it back to him. 'Juth was enthusiastic; you had to say that. But his judgement was all over the place. Always coming up with some shattering work of literature or another, always deeply average.'

'He was carrying this around in the hope of finding someone to give it to,' I say. 'I could have been anyone. He just caught me on my way out.'

'Don't suppose you fancy telling your story? Anonymous, of course. Can't really pay you, but y'know…'

He trails off. He knows by the expression on my face that it's not going to happen.

'Sorry,' I tell him. I'm not getting involved in their little revolutionary games. I respect their strength of belief and all that, but the simple fact is that if they ever became powerful enough to harm the Plutarchs or the Merchant Council, they'd be crushed flat. They exist only because they're beneath the notice of the powers that be.

'There's talk of a military push,' Barlan says, with affected nonchalance. 'Know anything about that?'

'I know they're not keeping it very secret.'

'They don't want to,' Pela interjects. 'They want to rally the troops and worry the Gurta. There've been enough false alarms though. Is this one real?'

'Your guess is as good as mine. I'm just a soldier.'

'You're Cadre,' she insists. 'You're inner circle with Caracassa. They trust you.'

'The aristocracy don't trust anyone, not even themselves,' I reply.

'There's a quote, right there!' Barlan cries. 'Can I use it?'

'No.'

'Anonymously?'

I sigh. 'My name turns up in print in any of your publications, I'll come find you.'

'Great!' he grins, and scribbles it down on a scrap of paper.

I look around the office. The other two are still watching me with undisguised suspicion and loathing. Difficult to decide if they're just playing revolutionary or if they have any muscle at all behind their politics.

'What's your take on the Korok thing?' I ask, wandering around the room, picking at this and that.

'Korok? Fucking whitewash, that's what that was,' Barlan mutters bitterly.

'I was there.'

He looks up, but it's Pela who exclaims: 'You were?'

'That's where I was captured. My husband was killed.' It's becoming easy to say now. I don't know if I should be pleased or saddened by that.

'Abyss! You're joking?'

'Does it sound like something I'd joke about?' I look at Barlan. 'You said it was a whitewash?'

He bursts into action all of a sudden, rummaging among the piles of paper scattered around the room. 'Look! If you're in any doubt that the Gurta knew our plans ahead of the attack, look at this.' He slaps a sheet onto a clear spot on one of the desks and smoothes it out. I recognise it immediately. It's a topographical map of the cavern where Korok lies, dominated by the lake in its centre. Coloured arrows and markers depict the movement of various forces around the landscape.

'How'd you get this?' I ask.

'We made it. It's compiled of eyewitness accounts from survivors, interviews with the soldiers who were there.' He catches the scepticism on my face. 'What, you think we can lift this stuff out of the Plutarch's records? We do what we can with what we have.'

'So what does this prove?' I ask, studying it.

'Just look at it. These here, this gang of Gurta bowmen? They were spotted moving towards this rise even before the soldiers they came to intercept were given the orders to go there. You see? They knew where the Eskarans were heading before our soldiers did.' He points to another spot on the map. 'Same thing happened here. There's just no way they could have reacted quick enough unless they already knew the attack was coming. You ever see Gurta this organised?'

I stare at the map. He makes a good point.

'They weren't even supposed to know you intended to take back Korok, but they'd placed explosives all over the port,' he says. 'They took out a ridge here and caused a landslide. Killed dozens of our people. And notice how they positioned the shard-cannon emplacements to overlook the areas where our troops were concentrated? That takes time to set up and supply. And look! Look how big the lake is! Think they could have got their ships from the other side that fast? Nah, they must have already had ships waiting in the lake even before Eskaran forces entered the cavern.'

I can feel something building inside me again as I gaze at the map: the anger, the frustration, the hate. I know the evidence is unreliable and yet I can't help but be convinced because I know how the game works and I know this is how it's played.

'Listen,' says Barlan, 'You swore your life to the high-ups and this may be hard to hear, but someone told the Gurta our plans. Someone important enough to know the tactics. That makes it a Warmaster at least, but most likely an aristo.' He shakes his head angrily. 'Someone sold us out. That's a fact. And you know what's worse? Someone could have told us who. But they got to him first.'

'Someone knew who the traitor was?'

'That was the rumour. Small-time merchant, he put out the word that he had evidence about some aristo dealing with the Gurta. But he was greedy. Wouldn't tell anyone until he got paid. He wanted to sell the evidence to the highest bidder, but he knew it was dangerous, so he tried to broker the deal through some crimelord out of Mal Eista. He got protection and a place to hide, and the crimelord was supposed to make the deal on his behalf in return for a cut of the money.' Barlan snarls. 'Fucking idiot. The traitor got to him, took him out before he could sell his little secret. All that stuff at Korok wouldn't have happened if that guy had just done the right thing.'

I can feel myself growing cold, and everything seems distant. My hangover has suddenly receded.

'What was his name?' I ask, but I already know his name.

'Gorak Jespyn,' Barlan replies.

Gorak Jespyn. The man I killed, quick and quiet, in his sleep, just like I was told to.

The traitor got to him.

8

'Who exactly do you think you are, Orna?'

The temperature in Ledo's private chambers seems to drop a notch. Suddenly I become very aware of myself, of the room around me. Swirled marble everywhere, gems inlaid in patterns on the floor, crystal columns through which clear waters flow. Behind where my master sits a four-legged beast is pawing the air. It's one of the half dozen sculptures in the room, all of them woven from hardened sap spun thin as thread, glistening in the light of the hooded lanterns. Ledo only keeps lanterns in his chambers. He doesn't like shinestones: he says the light makes everything feel cold.

Ledo looks up from the letter which he's barely read. A letter from the Dean of Engineers of Bry Athka University. This letter should open any doors that need opening, he'd said. Not this one, apparently.

Liss and Casta stand together at their brother's side. It's been some time since I saw them last, but they haven't altered in the interim, which is a surprise in itself. Liss is still pale and ragged and waiflike, Casta black-skinned, red-eyed and flame-haired.

I swallow against a dry throat and speak. 'Magnate, I'm only trying to explain how Jai would be more useful to you if he were-'

'I know what you're saying,' he interrupts me. 'Shut up.' He's more direct than I remember him. He's bulked out and turned his hair and eyes black, in stark contrast to his white skin. Perhaps it's the fashion now.

I wait for him to speak again, and as I do I glance at the twins. Liss is wringing her hands. Casta looks grave. After we pulled into the Veya trainyards I went home to change and grab the letter from the Dean before going to see the twins. They were kind and understanding, and they promised to do the best they could. But their best obviously wasn't close to good enough. Suddenly I have the feeling that this was a lost battle from the start.

'You forget your place, Orna, and you forget your son's,' he says, his voice low and gravelly where it was previously

high and soft. 'You are both in Bond to Clan Caracassa. The Bond is an obligation to submit to the will of your master, without question, without hesitation. Is that not so?'

'You didn't order Jai to join the Army-'

'Is that not so?' he barks.

'Yes,' I reply, bridling.

He sits back, satisfied that he has established his authority over me. As if it was ever in question. 'My sisters have explained your situation. I am not unsympathetic. Rynn was a great loss to us all. Your ordeal has been terrible indeed.' He taps his fingers on the stone armrest of the bench he sits on. 'But you forget your place. A Bondswoman does not lecture her master on how best to utilise those who serve him.'

'Magnate, I didn't presume to lecture, only to offer advice as to talents that may have escaped your notice. The letter in your hand testifies to his skill in engineering and invention. They're desperate to teach him. These are assets to the Clan that will be wasted if he is…' I can't bring myself to finish. 'I beg you.'

He sighs, but there's no real regret in it. 'Your motivations are transparent,' he says. 'If your concern for the Clan was so great, you would have raised this issue years ago.'

'That was my greatest mistake,' I reply, and the words taste bitter.

'The boy himself chose his path. He was allowed to join the Army because we prefer our people willing. He showed little enthusiasm for being an inventor, despite his talent.'

'That was because he wanted the approval of his-'

'Do you think you know better than your son what path his life should take?'

'I'm certain it's his wish as much as mine,' I reply, though I'm not at all certain. It's entirely possible he'll stick this course, even against his natural inclinations, out of loyalty to his father. I doubt it, but he might. The wishes of the dead become somehow sacred in a way they never were in life. That's why I want him to hear the news about Rynn from me, if he hasn't already found out. I want to talk to him, to persuade him to come back to what he values: to Reitha and the University.

The Skein of Lament

The Skein of Lament Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil

Braided Path 03 - The Ascendancy Veil The Ace of Skulls

The Ace of Skulls The Iron Jackal

The Iron Jackal The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray

The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr / the Skein of Lament / the Ascendancy Veil Storm Thief

Storm Thief Silver

Silver Pale

Pale Poison

Poison Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament

Braided Path 02 - The Skein Of Lament The Ember Blade

The Ember Blade The Black Lung Captain

The Black Lung Captain Out of This World

Out of This World The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3

The Braided Path: Ascendancy Veil Bk. 3 The Fade kj-2

The Fade kj-2 The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path

The Ascendancy Veil: Book Three of the Braided Path Retribution Falls totkj-1

Retribution Falls totkj-1 The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil

The Braided Path: The Weavers of Saramyr, The Skein of Lament and the Ascendancy Veil Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls

Ketty Jay 04 - The Ace of Skulls The Black Lung Captain totkj-2

The Black Lung Captain totkj-2 The Iron jackal totkj-3

The Iron jackal totkj-3 The Ace of Skulls totkj-4

The Ace of Skulls totkj-4 The ascendancy veil bp-3

The ascendancy veil bp-3